Finally Facing My Grief 20 Years Later After My Dad Died

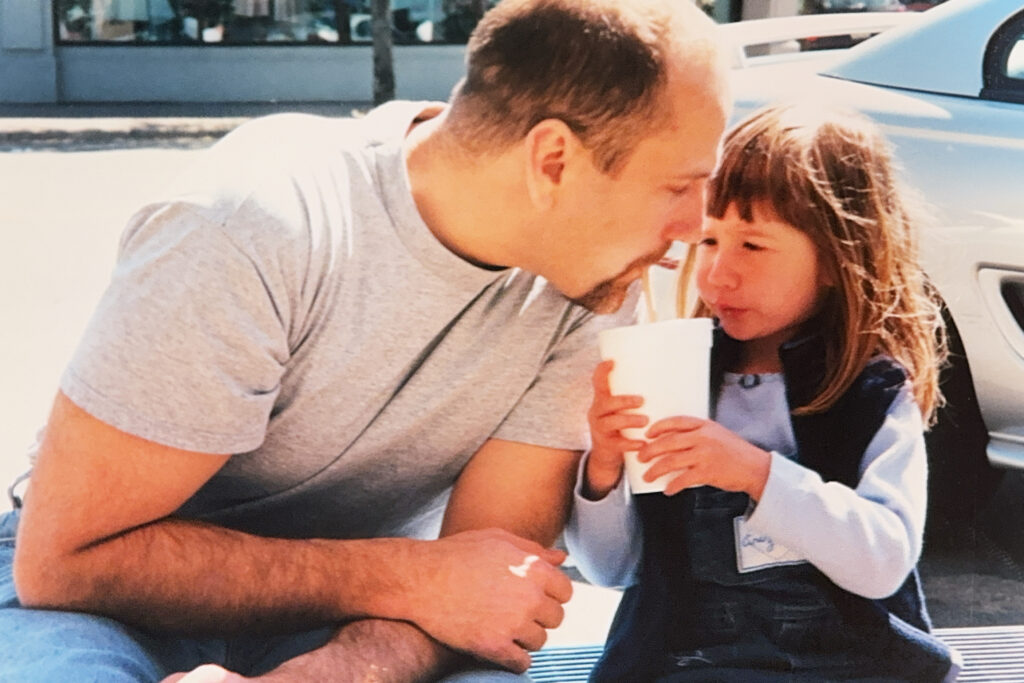

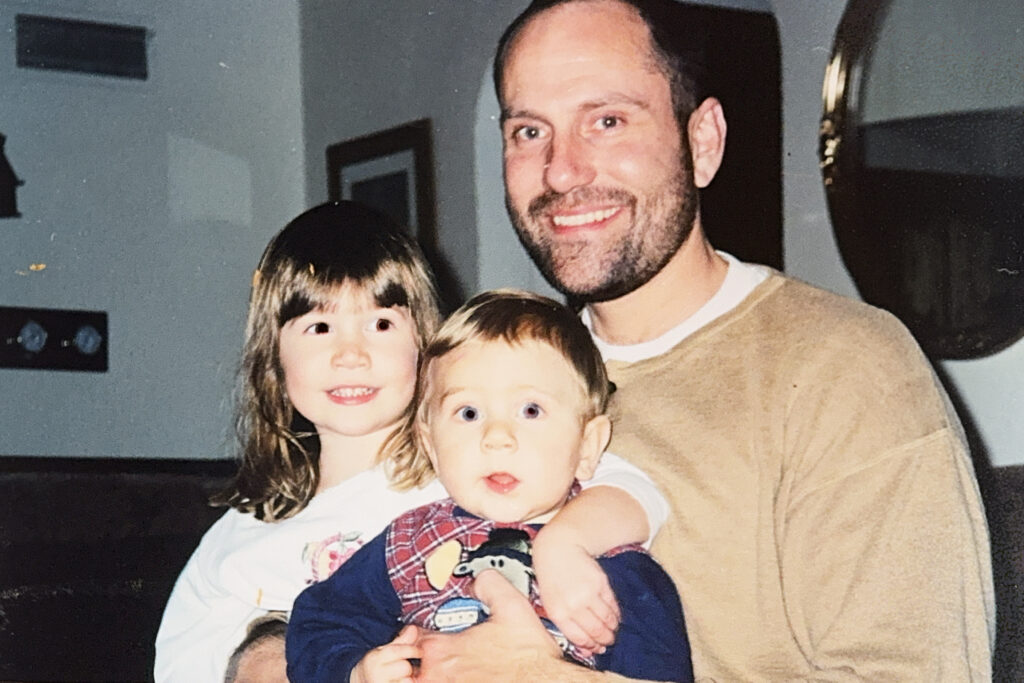

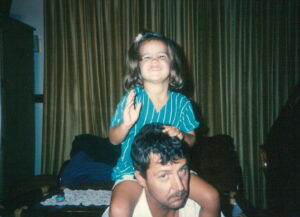

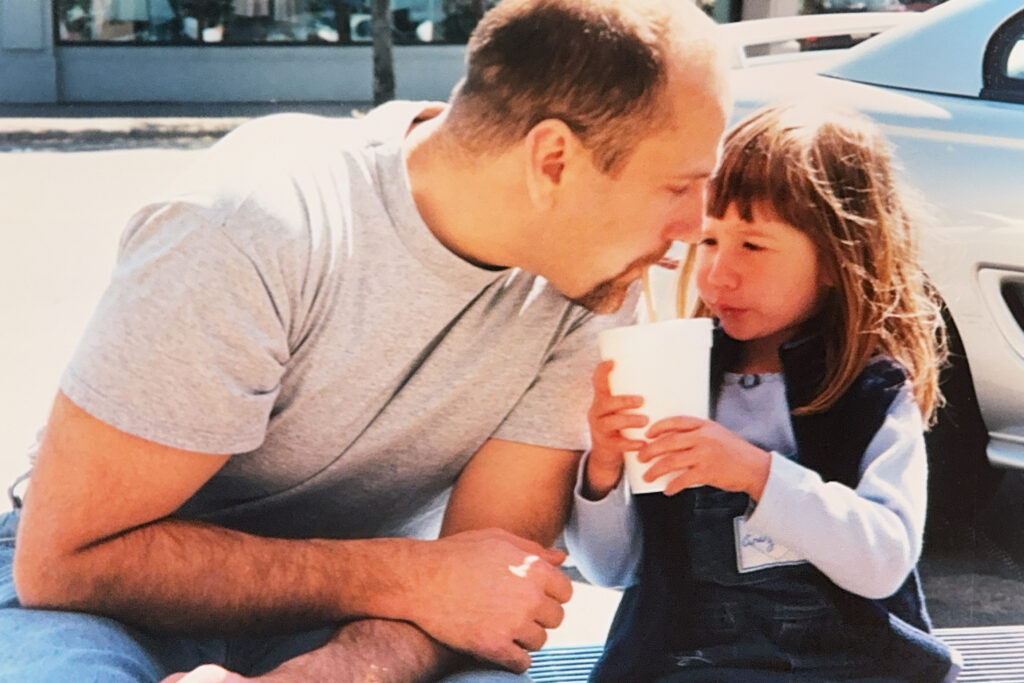

I was six years old when my dad died and twenty-five years old when I discovered Comfort Zone Camp. Everything in between has been a complex lesson on grief.

On Thanksgiving Day 2004, my younger brother and I survived a car accident that my dad did not. On the way to my grandparents’ house in Pennsylvania, a man on the other side of I-78 fell asleep at the wheel, crossing over the highway median and hitting our car head-on. Six people, including my dad, were killed. There were three survivors: me, my brother, and the driver that hit us.

On a day when I had anticipated to stuff my little face with Grandma Jane’s famous casserole and pistachio pudding, I sat in discomfort with salty tears and the taste of blood on my lips. With a severe concussion that knocked me unconscious on impact, I vaguely remember waking up in the hospital side by side with my brother. Strangers in scrubs under blinding, fluorescent lights hovered over us and told us that we were okay.

Even with my brother physically nearby, I was alone. From my perspective, the doctors got it all wrong – I was definitely not okay.

After learning that my dad had died, it felt like everything and everyone stopped being normal. People treated me like I was broken which confused me because I wasn’t. I survived. I was still me. I returned to school after winter break, flooded with notes from classmates and teachers with endless sentiments along the lines of, “I’m sorry.” I never understood why people say sorry after finding out about a death. All the attention made me feel loved and at the same time, empty and guilty. I hated feeling like my friends were sad because of me, like my dad dying was too hard for everyone else.

I was a burden.

Every day at school, I was made to feel like I had “dead dad” written in red marker on my forehead. Everybody overwhelmed me with kindness and grace, which probably wouldn’t have tasted as sour if it wasn’t so riddled with pity. I was treated differently than I was before. Friends cautiously stopped saying the word “dad” around me. Classmates nominated me as the class representative for fun school activities. Family members gave me extra Barbies on my birthday. All of the generosity in the world couldn’t have made it right. In all fairness, grief, PTSD, survivor’s guilt, and trauma weren’t taught to a bunch of sheltered, white upper-middle-class six-year-olds in Denville, New Jersey. We could barely do simple addition, let alone comprehend empathy. Things like this just didn’t happen to people like me in my small town. Everyone was trying their best but it wasn’t enough.

My mom remarried five years after my dad died and my childhood continued to feel like a whirlwind. Despite my stepdad being as accepting as any new father figure could, it wasn’t the family that was familiar to me. As I got older, conversations about my dad subsided. We’ve never been a big “talk about your feelings” family – at least not with each other. Every year on my dad’s birthday or anniversary of his death, the four of us would typically stop by the cemetery to lay down flowers and say a quick hello, then go out to dinner and clink our glasses together in an honorary “cheers!” This always felt comfortable. I was content with recognizing the sadness as each year passed and not feeling forced to talk about it. It always felt too complicated to talk about anyway.

During college, my appreciation for mental health advocacy grew. After years of watching my brother struggle with depression and fighting my own battle with anxiety, I felt a moral obligation to support others like us and many people close to me. The death of my dad at a young age forcibly taught me empathy, guilt, and hate at a level that many adults will never experience. In my discovered ambition to promote the emotional well-being of adolescents, I chose to study psychology.

I eventually sought a master’s degree in counseling on the school counseling track, where I was introduced to Comfort Zone Camp as a professional development opportunity for a class.

I first got involved with CZC as a Big Buddy volunteer. While I was intentionally there in a supportive role for my Little Buddy, my own personal grief skyrocketed. My eyes were riptides of tears the entire weekend watching kids open up and connect with others who understood what it was like to lose a parent. It was heartbreaking and unmistakably beautiful. I was reliving the death of my dad while some campers were processing for the very first time. It was the most reflection I had ever done as an adult, and to my surprise, it felt good. Being connected to others in the worst way made it hurt less. My heart ached in regret, wishing that I had gone to a program like CZC after my dad died.

I had gone my entire life being able to count on one hand how many people I closely knew that lost a parent. Suddenly, I was introduced to and embraced by an entire community of people like me.

After hearing about the CZC Young Adult camp, I signed up online with adrenaline and unease. I had watched the process of camp first-hand and it worked. The bubble was healing. I gathered the courage to face my fear, anger, and grief the way all those kids had. I wanted to be brave like them. In 14 years, I had never told my story out loud before. Outside of the routine, “My dad died in a car accident when I was a kid” statement when necessary, nobody legitimately knew. I told my story for the first time ever to a bunch of twenty-somethings who felt like immediate friends despite being strangers. Several of them had recently experienced a loss, while others were there in memory of a loved one who had died many years ago, just like me. I remember somebody had asked me if I was still mad at the driver that caused the accident. I think that there will always be a shadow of resentment towards the man who caused my family so much pain.

It’s a conscious effort to choose forgiveness and joy, but I think that’s what my dad would have wanted. My heart doesn’t have space for grudges. Life is too short to hold onto hate.

As I wrap up my second year as an Elementary School Counselor, I feel empowered by my grief in supporting this generation of kids. I approach every day with compassion. My dad dying was the worst thing that’s ever happened to me, but this life that I’ve built out of my experience allows me to do and be more.

Comfort Zone has allowed me to not only confront my grief but be supported and celebrated in it.

I am grateful beyond words to be part of a community that makes every day a little bit easier. I’d bet my dad would be proud to see me in my vulnerability and perseverance, no matter how long it took to get there. One step at a time.

By: Ada Tessmer