Walking Through Fog: Finding Light After Sibling Suicide Loss

I hate the question “how many brothers do you have?” Whether it comes up as a candid first-date conversation starter, in casual small talk with an Uber driver, or over lunch with colleagues, I never know how to answer: to keep the conversation fluid and pleasant and just say “three,” or to give the honest answer – “four, but one died” – and endure the awkward few moments as my conversation partner searches around for an “I’m so sorry!” or pivots away from the topic entirely.

People don’t ask me about my stepbrother Henry.

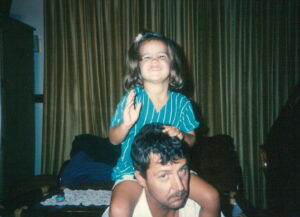

If they did, I would tell them that he was a larger than life figure (and not just because he stood well over six feet tall with a massive and unkempt shock of hair). He approached the world with an ebullient curiosity, enthusiastic love of learning, and absurd silliness – traits that could turn the dullest errands into thrilling adventures and make just about anyone smile.

He was an academic superstar – a member of our school’s state-champion mathletes and a computer science / art double major at Carnegie Mellon University when he died – but he wasn’t running the rat-race into which so many students at our fancy, Ivy-oriented suburban high school were forced. He loved learning, and especially numbers: His professors described his mathematical proofs as works of art, and the infectious enthusiasm he would bring to describing math problems demonstrated his intrinsic passion for the subject. And beyond academics, his authentic, quirky personality charmed everyone. He was goofy and creative in the best ways, and knew how to make people smile.

Henry and I did not have a close relationship. A socially awkward and deeply mediocre middle schooler, I was jealous of Henry’s seemingly effortless success academically, his innate skill at making great friends, and his vibrant personality. And for all of his great traits, he could also throw around casually cruel comments that cut me down. The last words we said to each other weren’t kind.

I was alone when I found out that Henry died. On the night of December 7, he posted his suicide note on Facebook. I saw it as soon as I logged on the next morning. A few hours later, my parents confirmed the news.

At the time, I was 14. A few months into my freshman year of high school – and struggling with friendship breakups, navigating my identity, and managing the intensity of adolescent emotions as a profoundly angsty and angry teen – I was already in a bad place before Henry died.

It was like the floor fell out from under me when I read his note.

The same way it’s hard to remember the bone-chilling winter cold in the middle of summer, it’s hard for me now to remember viscerally how I felt in the immediate aftermath of Henry’s death. I think I experienced a tornado of emotions: guilt that I hadn’t been kinder to him, rejected that I – and my family – hadn’t been enough for him, confused about why he took his own life, devastated about how deeply he must have been suffering, agonized that I’d never see him again, and furious at Henry and the world for making me hurt. But for the most part, I didn’t have the words to articulate or identify what I felt when I was 14. I remember being desperate for models and frameworks about how I was supposed to feel, and I wanted to know how to grieve in a way that wouldn’t make people uncomfortable.

In the weeks after Henry died, I didn’t have the space to process my feelings.

Amid the constant flood of people visiting with condolence lasagna, I felt like I had to be on my best behavior – when all I really wanted to do was rage out and break down. And when I returned to school, I had to numb my emotions because the world moved on for everyone else. None of my friends asked me about Henry or what the past weeks had been like. My teachers told me how to make up my schoolwork before the semester ended, but didn’t ask how I was doing. I didn’t even know how to bring up or begin discussing my grief in my weekly therapy sessions. Though I desperately wanted to talk about my loss, in classic teenage girl fashion, I didn’t want to say that I wanted to talk about it. I worried it was inappropriate to discuss Henry, and that I didn’t deserve to grieve because he was only my stepbrother, and not one I got along with particularly well.

In turn, I felt numb and distant as life “returned to normal.” I often felt like I was walking through fog.

I couldn’t focus in class or on my friends. I was a low-energy bummer: most of my friends stopped hanging out with me that year, and my grades plummeted. My already fragile mental health took a nosedive. Later that year I was hospitalized for suicidal ideation and struggled to control dramatic panic attacks whenever I felt overwhelmed. I was lucky to get a lot of help and support, including Comfort Zone Camp.

Comfort Zone Camp gave me a community in which I could express my grief and turn an awful experience into a chance to form meaningful connections with others. I first attended camp a little over a year after Henry died. I had always loved summer camp as a child, and the rustic, goofy atmosphere at CZC instantly felt familiar to me. At 15, it was easy to make friends at camp through shared eye-rolls at icebreaker games or during freetime Cards Against Humanity matches. And, surrounded by peers who “got it,” I could casually discuss my loss. It made a world of difference to have a weekend free from the stresses of school and home where I could focus on processing my grief.

Camp created magic that helped me connect with the intensity of my feelings.

Whether listening intensively to big buddy share or singing at bonfire or sharing at memorial service, I found some moments at camp profoundly special – and these moments enabled me to feel the depths of my loss in a safe and supportive space. Having the chance to feel my feelings and to share my narrative of my loss empowered me to move forward in a way that integrated my grief journey into the rest of my life.

After graduating from college, I returned to CZC as a volunteer. My return to camp was driven primarily by a desire to find community after college and to find ways to do good and stay grounded while I was working in the sterile and sometimes-alienating space of corporate America (and later law school). Over the past four years, I’ve been lucky to be a big buddy for so many amazing campers – each unique, resilient, and incredible in her own way.

While my campers definitely don’t need me around, it’s such a privilege to be there as they open up and discuss difficult topics, and it’s an absolute joy to see them return year after year. It’s evident that CZC has made a huge impact on their grief journeys, as I see returning campers discussing their stories more thoughtfully and comprehensively over time and becoming more empathetic and compassionate listeners in circle each year.

Even with the strength and skills CZC gave (and continues to give) me, I still struggle to figure out how to manage life as a sibling survivor of suicide loss in a way that is productive and balanced.

I still cry about Henry. I still agonize about how to discuss my grief in a socially-appropriate way, walking the line between being honest and vulnerable while not being a drama queen about my loss. It’s still difficult for me to talk about Henry with my family. Camp isn’t a panacea, but for me it’s been an invaluable support in my grief journey.

When I talk to my friends about Comfort Zone (and harass them to volunteer), I mostly hear two concerns: first, that they want to help, but worry that the experience would be too emotionally intense, or second, they feel massively under-qualified. I think those two concerns are misplaced. On the first, while camp has moments of emotional intensity, it also has moments of fun and silliness, and feels a lot like a classic summer camp.

Grief is part of the experience – but as in life, grief co-exists with goofiness and joy to create a more textured and full experience.

And on the second, I really think anyone can be a great volunteer – you don’t need to know what to say to a camper (there’s no right thing to say) or how to fix a problem, but just need to be willing to be there with them through the weekend and let them lead. I feel extremely lucky that I get to continue to be part of the Comfort Zone Camp community. It’s a place that has brought me so much joy, beauty, connection, and resilience over the years.

In many ways, it feels like a place where I can honor Henry’s legacy – trying to be sillier, happier, and more curious, just like he was – and I’m grateful to be able to give back in a small way to a place that made such an impact on me.

By: Izzy Baird